|

|

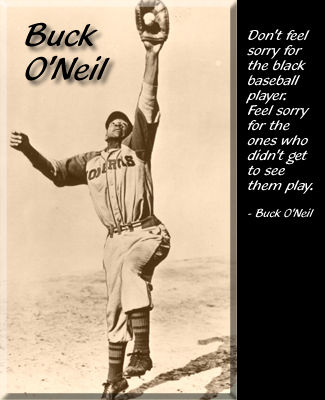

Don

Buford stayed in the same hotels as his teammates during road trips

(this was different than when he played with South Carolina just a few

years earlier). He perceived a more nuanced shift in racial attitudes.

while there was still hostility and racism, Buford detected something

else. By achieving on the field and interacting

with white fans, African American ballplayers had helped break down

ignorance and timeworn stereotypes. "Through

the vehicle of America's pastime, African Americans shattered Jim Crow

restrictions while simultaneously challenging long-held stereotypes

of racial inadequacy. The mere act of hitting,

fielding, and picking alongside white teammates and opponents, often

equaling or besting their feats, not only belied notion of black inferiority

but also signaled the eventual demise of Jim Crow."

"For

some, the prospect of watching blacks and whites interacting together

as equals for up to six months [in the minor leagues] was too much to

bear. Racists took their anger, fear, frustration,

and ignorance out on local black minor leaguers, hurling the vilest

of taunts their way. Their targets were hundreds of young ballplayers,

most of them in their late teens or early twenties. While learning to

hit a curveball or to catch a line drive, African American ballplayers

of the 1950s and 1960s also had to endure crude insults and degrading

living conditions. Yet they were still expected to perform at a high

level on the field. While some ended their careers in the South,

unable to bear up under the strain of racism and segregation, many persevered

and battled their way to the major leagues. The racial invective motivated

these ballplayers to excel and to demonstrate to whites that they were

tough enough to compete against white ballplayers and outplay them much

of the time."

"...the

most outstanding thing that summer was when it got so the players would

play catch with me. At first they'd be throwing the ball to each other,

and I'd be standing on the side. I started rolling the ball up on the

wire behind home plate and catching it when it came off. Then one day,

they said, "Get a bat. We'll play some pepper." I grabbed the bat and

started to pepper them. I was good at that. I hit it to each individual.

After that, they seemed to warm up to me. But I only felt accepted by

a few. When you're on a team and you're brushing shoulders with another

fella and he doesn't speak to you, it's kind of off. There were a few

guys who said little, to let me know they were friendly. They would

say, 'Don't worry, kid. Hang in there. You'll get 'em next time,' if

I hit a fly ball."

"Nobody

came up to me and said I wasn't welcome. But ignoring people is sometimes

worse than words."

"One

of the most disturbing things I experienced was the fact that there

were a lot of black players who had comparable skills to their white

counterparts, sometimes better, who were let go. This, the quota system,

really shook up people. They just were going to have so many blacks."

"While

their teams may have been integrated, not much else in their communities

was. Local laws and customs forced them to eat

and sleep apart from their white teammates. Most of the ballparks they

played in were segregated, with black fans being allotted seating in

cramped outfield bleachers. Some whites- fans, teammates, and

opponents- greeted their presence with racial epithets and slander.

Many white fans tolerated black major leaguers playing integrated spring

training games in their communities only because the players were there

for a very short time, not long enough to disrupt the social order." |

||||||||||||