|

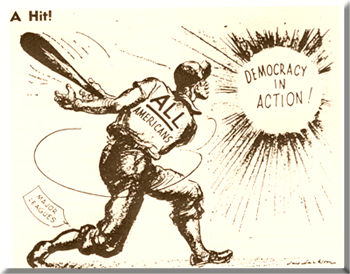

Courtesy The Chicago Defender, July 19, 1947.

|

"However,

in its support of baseball integration and in its treatment of black

athletes, the black press was at one with the black population. Never

acquiescing to segregation in baseball, the Negro newspapers conducted

a sustained campaign for sports integration that gave moral encouragement

to the black athlete and the black population." "In

1934, the Kansas City Monarchs became the first black team in the annual

Denver Post tournament... The invitation to the Monarchs was partially

the result of the campaign that was being waged by the black press for

full citizenship rights for black Americans. The bottom line, though,

was the promoters' recognition that a contest among the best teams in

the Midwest had to include the Monarchs." "The

call for integration reached a fever pitch by 1945, with some black

writers adopting showmanlike, theatrical methods to change opinion."

"With

justifiable pride, black

sportswriters pointed to the athletic and business achievements of the

Negro leagues. But the assumptions of segregation were challenged

most openly during the many interracial matches. Here,

within the narrow confines of the sports settings, black athletes met

the white man on his own terms and demonstrated their worth.

The victories undermined the very ideology of segregation and chipped

away at the status quo." "Behind

every victory many blacks saw a tiny step forward in their everyday

relations with the white majority. The Call's

sportswriter contended that the best thing that baseball did for Kansas

City was to allow the races to mingle and meet each other as fellow

human beings." "Writers

like Sam Lacy of the Baltimore Afro-American and Wendell Smith of the

Pittsburgh Courier had been crusading against the color barrier for

years. Their biggest obstacle was the commissioner

of baseball himself, Kenesaw Mountain Landis, a judge who publicly maintained

there was no discrimination in baseball and privately worked against

any effort to end discrimination." The

black sportswriters were "extraordinary men. Jackie Robinson said that

he could never have made it to the major leagues without Smith's help.

Indeed, their most lasting collective contribution may have been an

eloquent, persistent and occasionally bitter demonstration of words

designed to urge the white baseball establishment to integrate." "When

Ric Roberts of the Pittsburgh Courier asked the newly named commissioner,

Happy Chandler, 'What about the black boys?'

Chandler answered, 'If they can fight and die

in Okinawa, Guadalcanal, in the South Pacific, they can play baseball

in America.' But those were just words until Branch Rickey found

Jackie Robinson." |