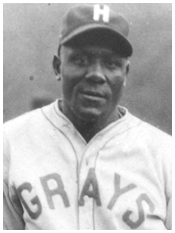

Ernest Judson Wilson

Nicknames: Jud, Boojum

Career: 1922-1945

Positions: 3b, 1b, 2b, ss, of, manager

Teams: military service (1918), Baltimore Black Sox (1922-1930), Homestead Grays (1931-1932, 1940-1945), Pittsburgh Crawfords (1932), Philadelphia Stars (1933-1939)

Bats: Left

Throws: Right

Height: 5' 8'' Weight: 185

Born: February 28, 1899, Remington, Virginia

Died: June 26, 1963, Washington, D.C.

National Baseball Hall of Fame Inductee (2006)

A savage, pure hitter who hit with power and was at this best in the clutch, Wilson could hit anything thrown to him and would have been an ideal designated hitter. Cum Posey considered him to be the most dangerous and consistent hitter in black baseball, calling him one of the stars of all time, and placed him on the all-time All-American team for a national magazine in 1945. So intense was his disdain and lack of respect for pitchers that he actually dared them to throw the ball. The left-handed slugger hit all varieties of pitching styles and all pitchers, including Satchel Paige, who considered him one of the two best hitters ever in black baseball.

The records bear this out as he consistently hit in the high .300s and even topped the .400 level on occasion. Beginning with a league-leading .373 batting average in 1923, he is credited with averages of .377, .395, .346, .469, .376, .350, .372, .323, .356, .354, .342, .324, .315, and .386 through the 1937 season. His career covered a quarter of a century, ending after the 1945 season, with a .345 lifetime average. He starred in Cuba for six winters, and his records there show a .372 lifetime average and two batting titles. Playing with Havana, he topped the league with averages of .403 and .441 during the winters of 1925-1926 and 1927-1928. His lifetime statistics in the Negro Leagues show an impressive .345 batting average, and against major leaguers in exhibitions the ledger shows a .442 average.

A product of the Washington, D.C., sandlots in the Foggy Bottom section of town, Wilson had a big upper body, a small waist, and was slightly bowlegged and pigeon-toed. Although he was awkward, he was fast and sure afield and, while lacking form, could play adequately at either corner. The rugged Wilson played third base by keeping everything in front of him, knocking the ball down with his chest, and then throwing the batter out, and was described as "a crude but effective workman."

A fierce competitor, hard loser, and habitual brawler, the bull-necked Wilson was fearless, ill-tempered, and known for his fighting almost as well as he is known for his hitting. Teammates, opponents, and umpires all feared the fury of the fiery-eyed, quick-tempered strongman. He was considered one of the "Big Four of the Big Badmen" of black baseball. The others accorded this designation were Chippy Britt, Oscar Charleston, and Vic Harris. Although his on-field conduct improved slightly as he got older, he never eliminated his need to exercise greater restraint in his behavior. He had the reputation as "the toughest man to handle in baseball." In 1925 this reputation led to his arrest on a "frame-up" assault charge. He was mean and nasty on the field, but when the uniform came off, he was a genial person off the field. He roomed with little Jake Stephens on the Homestead Grays, Pittsburgh Crawfords, and Philadelphia Stars, and they became very good friends. When he was in the last days of his life and unable to recognize anyone else, he recognized Jake by name.

But his good friend and roommate sometimes caused him problems. Once, when the pair were playing together with the Philadelphia Stars, Stephens was arguing with an umpire about a call, and Wilson intervened by positioning himself between the two parties as a buffer, keeping Stephens behind him and away from the ump. Stephens reached around him and hit the ump in the face, but the arbiter thought it was Wilson and put him out of the game. Wilson exploded, and the police had to come onto the field to subdue his fury. It took three policemen, freely using their blackjacks, to put him inside the patrol wagon and take him to jail. After being released he threatened to kill his little friend, and Stephens was so scared that he left town.

On another occasion, after the East-West All Star game in Chicago, Stephens came back to the room at about 2:00 a. m. after a night of carousing, and awoke the sleeping Wilson, who grabbed his little roomie and held him out of the sixteenth-story window by the leg while Stephens kicked his arm with his free foot. Wilson just changed hands, like a gunfighter's "border shift," with Stephens kicking and screaming sixteen stories above the pavement.

On the field, Wilson was vicious, and especially rough on umpires. Once he became so angered at umpire Phil Cockrell, a former player, because of a call that he made in a game against the Grays, that he grabbed the arbiter by the skin of his chest and lifted him off the floor, berating him for cheating them out of a game. His fury did not abate until his teammate "Crush" Holloway picked up a bat and interceded on behalf of the umpire. Only then did Wilson gain control of his temper and let the umpire go.

Wilson hated the bench almost as much as he hated umpires, and often refused to leave the lineup, even continuing to play with injuries that should have kept him out of action. In June 1924 he was playing first base for the Baltimore Black Sox and was hobbled by a bad ankle, but he insisted on playing. He crowded the plate when batting and was frequently hit by pitches. In the late summer of 1926 he was hit by pitched ball and suffered a cracked bone in his right elbow and was dedared to be out for the season. But against his doctor's advice, he was back in the lineup two weeks later and slammed 2 hits. A year later he suffered cuts when he and other Baltimore Black Sox players were in an automobile accident, but he refused to stay out of the lineup. But in June 1937 he failed to "dodge the bullet" when the Philadelphia Stars' team bus was hit by a car and his injury necessitated him missing an extended amount of playing time. Consequently his swing was impaired through the early part of the 1938 season. His distaste for being away from the action never abated, and on another occasion he played with three broken ribs. As late in his career as May 1940 he was injured and impatiently hurried his return to the lineup.

The esteem that he was accorded as a player is shown by a rumored trade that gained credibility in 1929, which would have sent him to the Homestead Grays in exchange for both Martin Dihigo and John Beckwith, two of black baseball's premier players.

When Wilson had his tryout with the Baltimore Black Sox, he earned the nickname "Boojum" because of the sound his line drives made when they hit the fence during batting practice. In later years he was described by the press as "probably the hardest hitter Negro baseball has seen." In 1922, his first year with the Black Sox, they were the champions of the South with a record 49-12, and he peppered the walls with base hits, batting a fantastic .522 through mid-August. Although the youngster was homesick and wanted to go back to Foggy Bottom at one point in the season, he stayed with the club for nine years.

During his career he was an integral part of teams that are easily identifiable as some of the greatest teams in black baseball history. During a six-year stretch he starred with the 1929 Baltimore Black Sox, the 1931 Homestead Grays, the 1932 Pittsburgh Crawfords, and the 1934 Philadelphia Stars. All four were championship teams, with the Black Sox winning the American Negro League pennant, the Stars taking the Negro National League pennant, the Crawfords claiming an unofficial championship, and the Grays winning a playoff for their championship. Wilson captained this Grays' team, which is considered by many to be the greatest black team of all time.

The demand for his baseball talents is exemplified by the 1932 season, when he began the year as the playing manager of the Homestead Grays but switched in turn to the Baltimore Black Sox and the Pittsburgh Crawfords in the regular season. Then, in the latter part of the season, he played with Black Sox again in a series of exhibitions against a major-league all-star team while being sought by the Kansas City Monarchs to go with them on their Mexican tour. The next season the East-West All Star game was inaugurated, and he was selected to the starting lineup for the first three classics after its inception, getting 5 hits in the games for a .455 All Star batting average.

He was appointed playing manager of the Stars in 1937 and, as would be expected, was a strict disciplinarian who did not tolerate loafing or grandstanding on the field. He hit a home run off the center-field fence to break a tie and win his first game as manager, and at the end of the first half of the season he was hitting .356. As a player he gave his best performance regardless of who was the manager, and he expected the same from the players under his authority. That season he beat Hall of Famer Ray Dandridge by a narrow margin in the All Star vote but did not play in the contest due to an injury. The next season, 1938, he lost to Dandridge by 27 votes, but Rev Cannady actually played in the East-West game.

After a .373 batting average in 1939 and three seasons under his belt as a manager, he left the Stars and joined the Homestead Grays during their glory years of the 1940s. The grizzled veteran was past his prime and didn't play full time in the latter years, but still hit for averages of .282, .340, .255, .350, .417, and .288 for the years 1940-1945, as the Grays captured Negro National League pennants every year after his arrival.

In the latter stages of his career he was afflicted with epilepsy and had to be hospitalized. In one World Series contest, the game had to be halted because he was in the field at third base, drawing little circles in the dirt with his finger and completely oblivious to his surroundings. After retiring from baseball, he worked for a road crew building Washington, D.C.'s, Whitehurst Freeway.

With a thirst for victory and a hunger for hitting, on the playing field Jud Wilson took a backseat to no one. His intense will to win and aggressiveness on the diamond added another dimension to his team value. He was posthumously inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 2006.

Source: James A. Riley, The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues, New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, Inc., 1994.

Jud Wilson